The ongoing civil conflict in Yemen erupted as a result of governmental weakness following popular dissent over systemic failure, unemployment and corruption. Internal fragmentation pre-existed as official authorities were at war with the Zaydi Houthi movement based on the northern parts of the country in the period 2004-2010. In the wake of the Arab Spring and as protests erupted, reconciliation efforts led by the GCC failed as Houthis were dissatisfied with the proposed territorial divisions and the solution put forward by the transitional government of Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. The proposed plan was one of the sparks that led to war and to this day, it is the only solution the official government accepts. The conflict between the two sides escalated when in 2015, a Saudi-led coalition invaded the country and engaged in a proxy war against the Houthis - who were supposedly assisted by Iran - by supporting the official government and other opposing sub-state actors. At the same time, southern separatist forces have also emerged, benefiting from the collapse of state structures, voicing demands for independence. Over the last two years, Saudi Arabia has been looking for ways to exit the conflict, while limiting the influence of Iran and the Houthis in the country.[1]

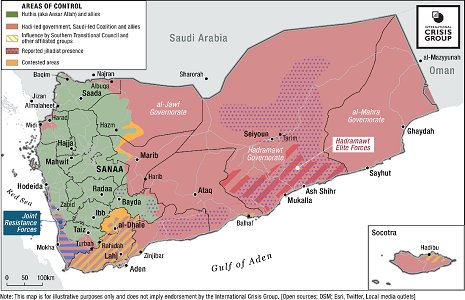

Following the signing of the Riyadh Agreement last November, there was a false optimism amongst the ranks of Saudi officials that the Hadi government and the STC would be able to form a coalition government and establish their authorities against the Houthis. Such expectations proved to be rather unrealistic as the two parties were unable to reach a compromise, and in April 2020, the STC declared its self-rule. Despite that, last summer, the southern separatists reaffirmed their commitment to the process, following efforts by Riyadh to reinvigorate the implementation of the Agreement. However, it was evident that the government had little to offer to the STC and that the 6 ministerial cabinets that would be appointed would have little impact compared to the possibility of independence and self-rule. [2] The STC has engaged in a limbo between its decision to cooperate with Hadi and following its own path. In late August, the southerners withdrew once again from the Agreement due to the resumed fighting in the southern Abyan governorate and the collapse of public services in the area, where public officers remained unpaid by the central government for six months.[3] These efforts were also hindered by internal divisions in the southerners’ camp. In areas where local identity plays a greater role than central authorities, even the STC had little leverage. While in northern Hadramawt, the main STC-leaning force is the UAE-backed Elite Hadrami Forces, locals were also organized around two opposing fronts: the Hadramawt Inclusive Conference which is pro-unity and Fadi Baoum’s Supreme Hirak Council and the Revolutionary Council of Al-Hirak in the southern cities of Mukalla, Shabwa and Aden.[4] Saudi Arabia also has a stronghold in the area as it was proved in 2015, when 95 sheikhs from local tribes signed a petition demanding Saudi Arabia to annex Hadramawt, Mahra and parts of Shabwa, following Saudi encroachment in neighboring Mahra.[5] Thus, although the Agreement was aimed at bringing together the government and the southerners, it was ignoring conditions on the ground and more powerful local actors, with agendas conflicting to the STC and little incentive for cooperation.

Looking into the “unclaimed” governorates, Marib has been characterized by many as the key to the end of the war as it would lead to the complete control of the northern parts of Yemen by the Houthis, it would expose the inability of the government to support its allies and it would hinder the political process led by the UN. Taking over Marib would also create a path for the Houthis to the east and provide an easy road to the area’s oil refinery and to Al-Mahra, Hadramawt and Shabwa. All the above justify the interest of the Houthis, who launched an attack on the governorate in early 2020, with fighting persisting to this day. Since the beginning of the war, Marib and its leading tribe, the Murads, who are dedicated Sunnis and are thus strongly opposed to the Zaydi movement, was able to largely maintain its independence from both sides and sustain its structures, while benefitting from its oil and gas revenues, which also posed a temptation to all conflicting parties interested in taking advantage of the governorate. The Hadi government relied on the Murad’s resentment towards the Zaidi movement and forged a –yet unstable alliance- with the tribe in order to take Marib under its own control. This alliance proved rather difficult to maintain as the central authorities were unable to respond to the demands of the Murads during the infighting in Marib. In turn, the tribe withdrew its troops supporting governmental forces across Yemen in order to strengthen their position in their own lands.[6] When in September the Houthis attacked and easily took over areas in the northwest and south of the governorate, it was evident that the balance had shifted. This attack resulted in the takeover of the southern city of Rahabah with an agreement signed between tribes from the Murad confederation and the Houthis. The deal was an indication of the dissatisfaction within the governmental alliance due to the inability of the government to address people’s expectations and a symbolic move signaling that, for the tribes, maintaining their sovereign rule was more important than good relations with central authorities. Developments in the area shed light on the weaknesses of the government and the Saudi-led coalition, which failed to support their tribal allies.[7]

Marib has been particularly important for the evolution of Saudi involvement in the area as losses in the governorate have led to the dismissal of Saudi commander Prince Fahd bin Turki and the gradual disengagement of troops from the area, which in turn move to the southern borders of Saudi Arabia with Yemen.[8] The war of attrition that is currently taking place in the governorate has been a clear indicator for Riyadh that the final outcome of the war would be decided on a local level and the withdrawal of the troops to the country’s borders shows that Riyadh is finally coming to terms with the fact that there are limited gains in the conflict and has failed to turn it to its flagship in the race for the leadership of the Gulf.

The situation is similar, yet even more complex in the south-west Taiz governorate, where the anti-Houthi front is further divided. While Islah holds the lion’s share when it comes to influence in the governorate, its authority is disputed by forces of Tareq Saleh that control the coastal areas of the governorate as well as several other local actors. Tareq Saleh’s Giant’s Brigades and National Resistance Forces that have developed across coastal Taiz and south Hudeydah enjoy the support of the Emiratis, who also provide assistance to the renowned Nasserist-leaning 35th Armored Brigade controlling Al Hujariah in the south and Salafi Abu Al-Abbas Brigades in the west of the governorate. What is most interesting regarding Taiz, is that its diversity of local actors has drawn different Gulf states that aim to increase their influence by aiming to smaller forces, yet holding more power at a local level. Besides the U.A.E., Qatar along with Oman support Sheikh Hammoud Al-Mekhlafi, an Islahi who resides between Istanbul and Muscat and recently called for troops to capture Taiz city from Houthi forces. Al-Mekhlafi is considered a threat by both the U.A.E. and Tareq Saleh, while his claims were also condemned by Islah in an effort to appease Saudi Arabia.[9]

Albeit Saudi Arabia is the sole Gulf power predominantly engaged in the Yemen war, Riyadh has failed to address the complex dynamics on the ground, investing in a comprehensive yet inadequate solution like the Riyadh Agreement. In contrast to its fellow Gulf states, Saudi Arabia has been supporting the central governance of Abdrabuh Mansur Hadi and has been promoting a pathway of cooperation with the STC. Such an approach has proved to be rather ineffective, as Riyadh had the capacity to bring parts to the table, although lacking the means to force the implementation of the terms agreed, while also having little experience in negotiations per se.[10] What has been clear over the last year is that Saudi Arabia has realized that there is no end in sight for the war in Yemen, at least not one that would lead to the defeat of the Houthis. Thus, it is trying to promote a political settlement that would hinder the dominance of the pro-Iranian non-state actor, which would be considered an existential threat for Riyadh, as well as secure its border.[11]

Five years since the intervention of the Saudi coalition in Yemen and a year since the signing of the Riyadh Agreement, little has changed, and conditions on the ground are dire for most Yemenis. Houthis have largely consolidated their authority in the north and have achieved advancements in certain fronts, particularly over the last year. On the contrary, the anti-Houthi alignment is deeply divided and comprises mostly local actors with individual agendas and internal rivalries that do not allow for comprehensive action against the movement. At the same time, the government has proved fairly weak and unable to fulfill its promises towards its bitter allies. This situation has favored the rise of more localized actors that establish a status quo where tribal identity and material interests create de facto divisions amongst all camps. As Saudi Arabia is trying to disengage from the war and its fellow Gulf states pursue their own agendas, reality on the ground will possibly become permanent, leaving little room for future negotiations for the end of the war and the possibility of a united Yemen.

All links accessed on 28/11/2020.

[1] International Crisis Group, “Rethinking Peace in Yemen”, Report No 216, July 2, 2020, https://bit.ly/36grxGR

[2] Sana Uqba, “Yemen in Focus: Houthi offensive on Marib could determine country's future”, The New Arab, September 4, 2020, https://english.alaraby.co.uk/english/indepth/2020/9/4/yemen-in-focus-the-battle-for-marib

[3] Middle East Monitor, “Yemen southern separatists withdraw from Riyadh Agreement talks”, August 27, 2020, https://bit.ly/36gfOYO

[4] Hussam Radman, “Addressing the Southern Issue to Strengthen Yemen’s Peace Process”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 6, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/11634

[5] Franck Mermier, “Yemen's Southern Secessionists Divided By Regional Identities”, Italian Institute for International Political Studies, March 20, 2018, https://bit.ly/3g3UrgN

[6] Maged Al-Madhari, “Marib’s Tribes Hold the Line Against the Houthi Assault”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 5, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/11617

[7] Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “Battle for Marib”, The Yemen Review, September 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/11678

[8] Ibid.

[9] Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “Taiz at the Intersection of the Yemen War”, March 26, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/9450

[10] Elena DeLozier, “Saudi Leverage Not Enough to Achieve Peace in Yemen”, The Washington Institute, April 29, 2020, https://bit.ly/3o8koP3

[11] International Crisis Group op.cit