Today's era is characterized by constant rearrangements and changes, which have always happened in the past as this is a natural progression of events. However, now it seems to have acquired a reckless speed of change similar to that of the development of technology, which is undoubtedly judged as one of the most important game changers of international reality. The ambiguity and multipolarity that characterizes contemporary events and international developments tend to become a constant among the maze of variables, making it increasingly difficult to properly and qualitatively analyze and design an effective plan of action at the nation-state level.

Today's era is characterized by constant rearrangements and changes, which have always happened in the past as this is a natural progression of events. However, now it seems to have acquired a reckless speed of change similar to that of the development of technology, which is undoubtedly judged as one of the most important game changers of international reality. The ambiguity and multipolarity that characterizes contemporary events and international developments tend to become a constant among the maze of variables, making it increasingly difficult to properly and qualitatively analyze and design an effective plan of action at the nation-state level.

Approximately half of the 59 million people living in the six member-states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) are immigrants. Some remain for a few years, while others stick there for their whole careers. The majority enters the country based on the assumption that they will have to leave eventually. Despite their numbers, migrants have restricted rights in the Gulf states' destination countries: they have temporary residence and limited involvement in society. The prospect of granting citizenship to foreigners has long agitated the Gulf states. For the vast majority of foreign employees, life in the Gulf consists of a succession of short-term work permits; by stop being productive, you stop being a resident. Nevertheless, this situation is gradually and slowly changing; the need for diversification of the economy has forced some of the Gulf states to break this citizenship taboo.

Approximately half of the 59 million people living in the six member-states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) are immigrants. Some remain for a few years, while others stick there for their whole careers. The majority enters the country based on the assumption that they will have to leave eventually. Despite their numbers, migrants have restricted rights in the Gulf states' destination countries: they have temporary residence and limited involvement in society. The prospect of granting citizenship to foreigners has long agitated the Gulf states. For the vast majority of foreign employees, life in the Gulf consists of a succession of short-term work permits; by stop being productive, you stop being a resident. Nevertheless, this situation is gradually and slowly changing; the need for diversification of the economy has forced some of the Gulf states to break this citizenship taboo.

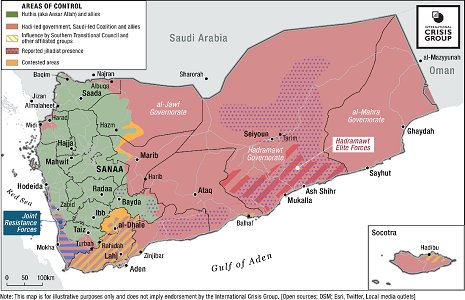

Almost 6 years since the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen, the long-term and largely neglected conflict, is still going strong, albeit turning to several internal conflicts between local actors benefiting from the weakness of central government and the numerous divisions of societal and state structures that favor the prevalence of local authorities. Even though frontlines have not changed significantly over the last couple of years and most local actors have established their authority in certain regions, the war has not been called and conflict persists in key areas of the country. In the governorates of Marib, Taiz, Hadramawt and Al- Hudeydah, clashes persist and neither of the two main conflicting parties has consolidated its authority in these areas, despite Houthis gaining significant ground over the last year.

Almost 6 years since the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen, the long-term and largely neglected conflict, is still going strong, albeit turning to several internal conflicts between local actors benefiting from the weakness of central government and the numerous divisions of societal and state structures that favor the prevalence of local authorities. Even though frontlines have not changed significantly over the last couple of years and most local actors have established their authority in certain regions, the war has not been called and conflict persists in key areas of the country. In the governorates of Marib, Taiz, Hadramawt and Al- Hudeydah, clashes persist and neither of the two main conflicting parties has consolidated its authority in these areas, despite Houthis gaining significant ground over the last year.

Recently, Israel has improved its relations with the Gulf. This development was formalized via the Abraham Accords with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain and the silent approval of Saudi Arabia. The normalization between Israel and the Gulf is the result of a process some 20 years in the making, as 27 years have passed since Rabin, Arafat and Clinton signed the Oslo Declaration of Principles, which for the most part is now inactive. The questions that arise are how these accords can potentially affect the regional balance and whether more accords are likely to come.

Recently, Israel has improved its relations with the Gulf. This development was formalized via the Abraham Accords with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain and the silent approval of Saudi Arabia. The normalization between Israel and the Gulf is the result of a process some 20 years in the making, as 27 years have passed since Rabin, Arafat and Clinton signed the Oslo Declaration of Principles, which for the most part is now inactive. The questions that arise are how these accords can potentially affect the regional balance and whether more accords are likely to come.

Israel’s normalizing relations with various Arab countries brought the Palestinians once again before the bitter realization that time is working against them. It appears that this realization triggered a process of reconciliation among the Palestinians. Yet, will these efforts suffice to influence the course of the Palestinian Question within a rapidly changing regional environment?

Israel’s normalizing relations with various Arab countries brought the Palestinians once again before the bitter realization that time is working against them. It appears that this realization triggered a process of reconciliation among the Palestinians. Yet, will these efforts suffice to influence the course of the Palestinian Question within a rapidly changing regional environment?

Protests across Sudan are well into their fourth month, consistently defying President Omar al-Bashir’s suppressive response, as well as his superficial political appeasing efforts. That persistence, stemming from economic and political demands highly similar to those expressed in several Arab countries during the so-called “Arab Spring”, interestingly underscores a relevant continuity of the transformative dynamics that emerged back in 2011. In Sudan, similar peaceful revolts have twice -in 1964 and 1985- ended up in the collapse of military dictatorships. Nevertheless, despite the protesters’ determination, the existence of a particularly rigid pro-status quo regional political landscape further complicates the equation that could lead to actual political change.

Protests across Sudan are well into their fourth month, consistently defying President Omar al-Bashir’s suppressive response, as well as his superficial political appeasing efforts. That persistence, stemming from economic and political demands highly similar to those expressed in several Arab countries during the so-called “Arab Spring”, interestingly underscores a relevant continuity of the transformative dynamics that emerged back in 2011. In Sudan, similar peaceful revolts have twice -in 1964 and 1985- ended up in the collapse of military dictatorships. Nevertheless, despite the protesters’ determination, the existence of a particularly rigid pro-status quo regional political landscape further complicates the equation that could lead to actual political change.

Το Κέντρο Μεσογειακών,Μεσανατολικών και Ισλαμικών Σπουδών φιλοξενεί πληθώρα διαφορετικών απόψεων στα πλαίσια του ελεύθερου ακαδημαϊκού διαλόγου. Οι απόψεις αυτές δεν αντανακλούν υποχρεωτικά τις απόψεις του Κέντρου. Η χρήση και αναπαραγωγή οπτικοακουστικού υλικού για τις ανάγκες της ιστοσελίδας του ΚΕΜΜΙΣ γίνεται για ενημερωτικούς, ακαδημαϊκούς και μη κερδοσκοπικούς σκοπούς κατά τα προβλεπόμενα του Νόμου 2121/1993 (ΦΕΚ Α' 25/4-3-1993) περί της προστασίας της πνευματικής ιδιοκτησίας, καθώς και του άρ.8 του Νόμου 2557/1997 (ΦΕΚ Α' 271/1997).